We try, seasonally, to sit down and do some reflection and goal-setting as a family. A few weeks ago, as school was beginning, we gathered in the front room and did some big, bucket-list brainstorming. Lots of wonderful ideas ensued, some fanciful, others more practical: visit every state, learn to speak French, adopt a rescue dog, take all the AP classes, live in an apartment with my cousin, beat Minecraft, go on a long roadtrip with friends, walk the Nestucca River from Elk Creek to Rocky Bend, graduate from college, find a job I love, swim across the Columbia, buy a house, attend the World Cup, ride in a hot air balloon, and many, many others. We laughed and had fun; we nodded and agreed; we were dreaming together, delighting in one another’s particular delights and wild plans.

The next steps, of course, are harder. How best to portion and plan a dream? How do you day after day keep delight alive? How might we fix that bright, necessary star in our eye? “Your job,” writes William Stafford, in his poem “Vocation,” “is to find what the world is trying to be.”

Since finishing edits on The Entire Sky, I’ve been trying, and mostly failing, to get a new novel underway. I’ve been scribbling on a number of possibilities, but can’t yet seem to find my way to the heart of any of these projects; I haven’t yet found or seen or understood what these worlds are trying to be.

I was raised a ranch kid, though, and, inspired or no, if there’s more fence to fix, well, you fix fence. So, as the days darken and the rains fall here in the Willamette Valley, we’ll sit down again and revisit these and other goals, begin to plan our way toward them. And though I’ll offer what I can, I simply won’t have any answers for my children—save to keep dreaming, to keep working, to stay awake and be every moment on the lookout for the way forward.

The Book Tour Continues

From a lovely run through the mountains of western Montana to a graduate school reunion in Idaho and just lately closing the Sisters Saloon down with John Larison and Willy Vlautin, the last month and change have been all kinds of wonderful. And I’m not hanging up my spurs just yet! Love to see you in the coming weeks in Corvallis, Canton, Brooklyn, McMinnville, Bend, Salem, or Portland.

The Entire Sky Book Tour: A Reading with the Spring Creek Project September 20 at 7:00 pm – 8:00 pm, Patricia Valian Reser Center for the Creative Arts, Corvallis, OR

The Entire Sky Book Tour: St. Lawrence University Writers Series September 24 at 8:00 pm – 9:30 pm, St. Lawrence University, 23 Romoda Dr, Canton, NY 13617

On America: A Reading and Conversation at the Center For Fiction with Essie Chambers, Julia Phillips, and Joe Wilkins, moderated by Nina St. Pierre, September 25 at 7:00 pm – 9:00 pm, The Center for Fiction, 15 Lafayette Ave, Brooklyn, NY

The Entire Sky Book Tour: Readings at the Nick, October 1, 2024 at 5:30 pm – 6:30 pm, Linfield University, Nicholson Library, McMinnville, OR

An Evening with Ellen Waterston and Joe Wilkins, Roundabout Books in Bend, OR, October 17, 2024 at 6:30 pm – 7:30 pm

An Evening with Scott Nadelson and Joe Wilkins, The Book Bin, Salem, OR, November 1, 2024 at 5:00 pm – 6:00 pm

The Entire Sky Book Tour: Portland Book Festival, Event Times and Places TBA, November 2, 2024

A Favor

On my travels and over email I’ve heard such wonderful things about The Entire Sky. If you’ve read the book and feel so inclined, a review on Goodreads or Amazon goes a long ways. Thanks!

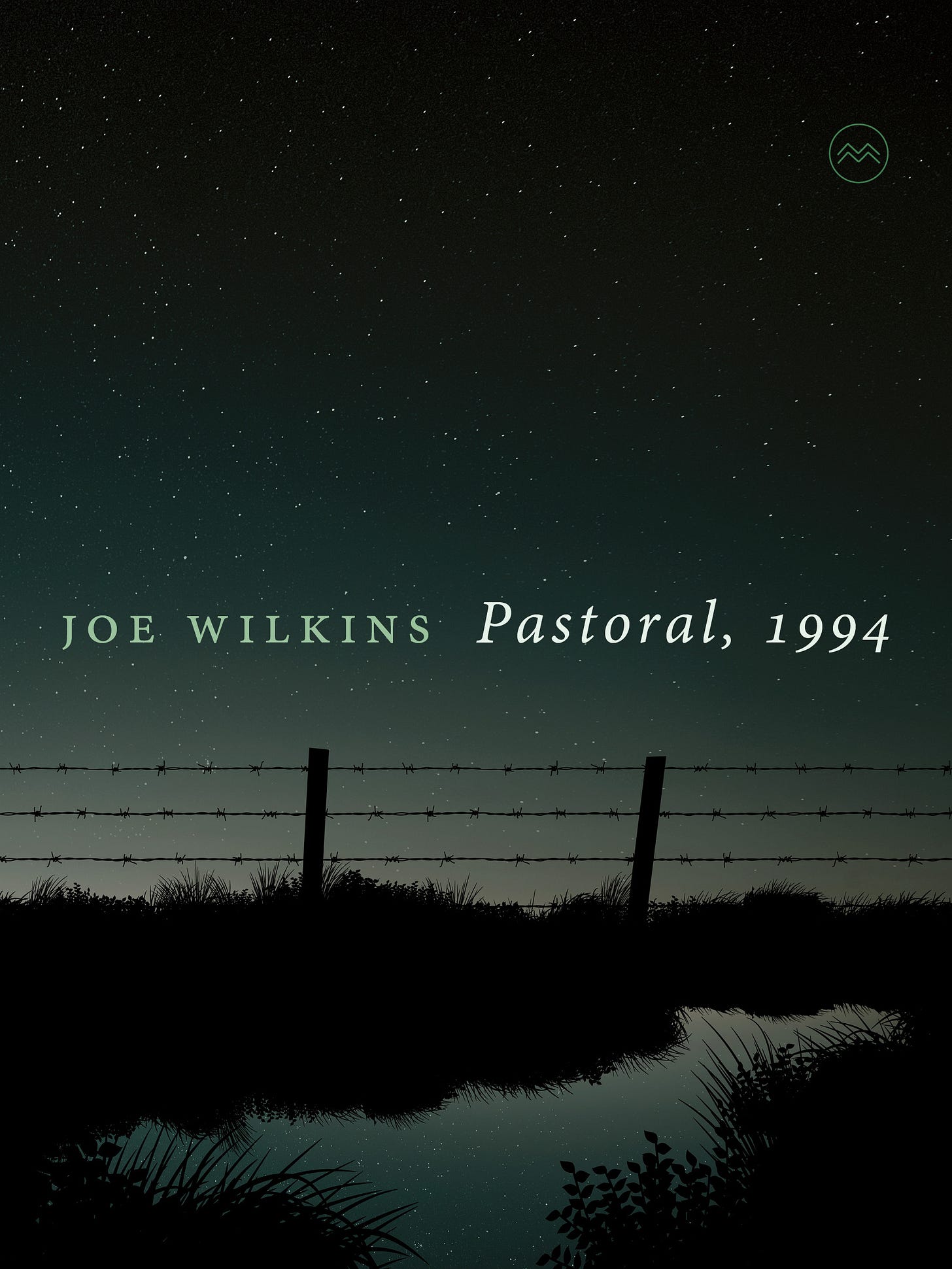

Pastoral, 1994

In early 2025, River River Books will publish my fifth full-length collection of poems, Pastoral, 1994. We’ve got a cover now, and the good words below from some of my absolute favorite poets are totally humbling and amazing. You can read a few poems from the manuscript in the latest issue of On the Seawall.

Joe Wilkins grew up in flyover country, or drive-by-and-never-imagine somebody might actually live there country. If pastoral literature idealizes agrarian life, Joe Wilkins means both to assent to that idealization and repudiate it simultaneously. Everyone’s life is encoded in blood, but we should also know that in the hands of a poet like this one, life is also encoded in words, words the poet deploys to enliven the past that made him. Consider the grasshoppers in a jar by the boy’s bed. He likes the noises they make at night. He knows, if you hook one at the thorax and toss it in a pond, it will twitch, even weighted to the bottom, for hours. It’s another thing he never forgets. Read “Dirt Song.” Just eight lines long. But listen, just listen to what it sings. -Robert Wrigley, author of Box and The Lives of the Animals

There’s much to say about toxic masculinity, but nothing clarifies the matter more than our boys, especially our heartland, heart-wrung boys, those boys once so tender as to practice kissing by kissing other boys in ditches like those they would later dig. Because these are the boys of Joe Wilkins’ poems—forged by machine shop and rifle rack, by locust-destroyed crops and beetle-killed pines, by grain augurs and crop dusters, by the endless elegies of cancer and farm foreclosures. And their story—which is largely Wilkins’ story—as told in Pastoral, 1994—radiates with such plainspoken vulnerability we can’t help but empathize. As he writes, ‘We believed, as all children do, / that we were a beginning,’ and this drought-ravaged, barbwire-scarred portrait burns their beginning deep into the skin of the reader, leaving a brand that marks our love for them, that says we forgive even the brutal mistakes they might grow up to make. -Nickole Brown, author of To Those Who Were Our First Gods and Fanny Says

The poems in this stark and brooding collection invite the reader to consider the long-range landscape of the upper Great Plains. It’s both a place and also a measure of Time. And the poems here people this place with working people, who necessarily live in this measure of Time. In their time, the people are loyal, fallible, vulnerable, subject to love and confusion. These are real poems, based not on feelings, but on hard things, like raw lumber and barbed wire, new-born lambs and drought, shovels and dirt, fire and dim light. Rightly and beautifully, the poems in this pastoral book do not register a land of plenty, but a land of toil and loss, both a truth and a lament for rural America. Despite all of our efforts, we must live with plight, wherever we are—a plain fact this book conveys with beauty and fine-tuned detail. I admire the lines, the phrasings, the imagery, the music, and the living art of these poems. -Maurice Manning, author of The Gone and the Going Away and The Common Man

The poems of Pastoral, 1994 follow a map back to a place and time which, like “the names of gods no one believed in anymore,” exists now mostly in memory. But though longing naturally permeates Joe Wilkins’ elegies to the small agricultural communities of Eastern Montana, the greater ethos is one of confusion and dissonance: what to call the distance between the self and the former self, whether that self be a town or a man who has outgrown its dot on the map. While Western writers like Hugo and Wrigley might seem to be the forbearers of such work, it’s the careful music and respectful rhythms of Heaney that I hear in these meticulous and potent lyrics. Masterful and generous, Wilkins works to make sense of his memory of the world not as a thing pinned down, inert, but still alive—as the past always is for us—even in dirge, even as we stand, stunned and reeling, at the wake. -Keetje Kuipers, author of All Its Charms and Beautiful in the Mouth

And I figure you’ll want to check out this big old volunteer pumpkin that grew in our front flowerbed. It’s just starting to turn orange!

Loved meeting you at the Sisters Festival of Books last weekend. Look forward to reading more of these posts and The Entire Sky!

Wishing all these and more good things Joe. Congrats on the new poetry book. And thanks for inspiring this poet to also follow some fiction stories - I woke up with a fictional short story in my head the other morning, clear as day, which hasn't happened in years.